As an academic, I am able to “use GIS just for fun” all the time, and I take every opportunity to do so. This is often in the form of homework assignments, so let me share the most recent. It reads as follows.

Kroon Hall’s north courtyard is once again being revamped, this time by way of a generous gift from the ENV755 Class of 2025. The donors have proposed that this entire space be devoted to a distinctive sculpture, one that not only reflects well on them but also on the School - particularly as both School and sculpture respond to changing environments, activities, and perspectives.

To help meet that challenge, your task is to indicate how this sculpture should be colored. You are welcome to use whatever colors you’d like, but their pattern must be derived from the sculpture’s form.

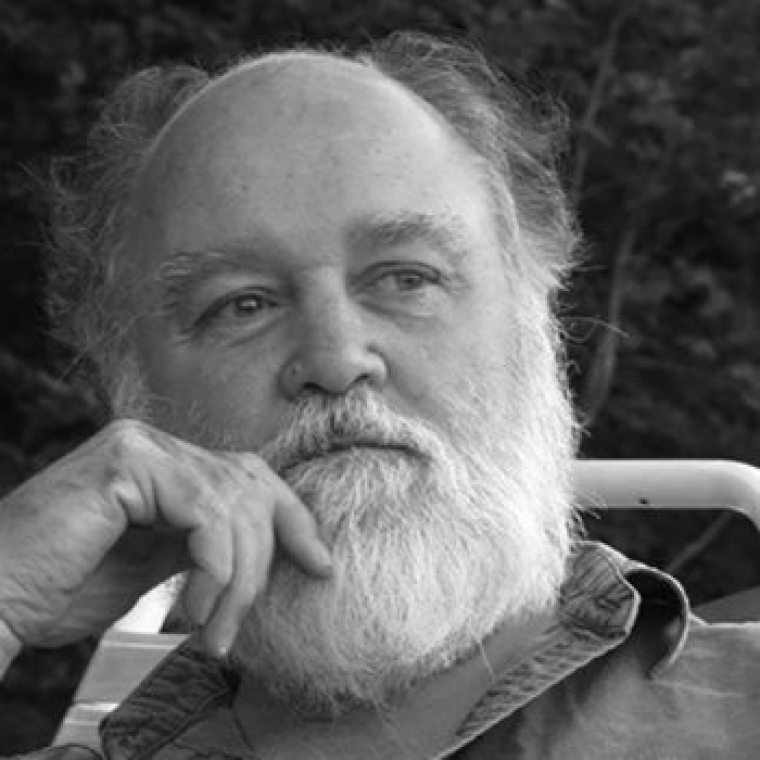

It’s a maddenly open-ended assignment that becomes considerably less so when students start to tinker with that (deliberately sculpted) sculpture. As they begin to subject it to various topographic transformations, the resulting patterns begin to resemble to their own smiling faces. The fun for me in all this lies not so much in the initial dad (or uncle) joke as in the “How did you do that?” question that follows and, much more significantly, that unmistakable twinkle in eyes of those who eventually get it. And are beginning to get hooked.